In our last blog, we shared some of our thoughts and experiences around what happened when an MVP is less than minimal. This typically happens where mature organisations are re-platforming, or new organisations launch a challenger proposition into a mature marketplace. Where the ‘Minimal’ is significant in terms of size from the outset, this can create challenges like de-motivation, lack of confidence and, ultimately, paralysis.

In this blog, we’ll share our thoughts and experiences on the ‘V’ in MVP – viability. We’ll look at why viability has become increasingly difficult to determine and how this concept fundamentally challenges our understanding of organisational value.

The variables of viability

A critical part of determining the ‘Minimal’ aspect of a product is defining what we mean by ‘Viable’. The interplay between both ‘M’ and ‘V’ elements of the MVP is complex and frequently the ‘V’ ends up challenging the ‘M’. In simple terms, viable should be the smallest thing of value that will test the proposition. On that basis, we want to test the proposition in the simplest, fastest and cheapest possible way, but there is an assumption that the proposition is viable at this point, i.e. it is capable of working successfully. It is in this nuance that many organisations become lost.

For established businesses, marketplaces and mature organisations, even when launching a brand-new product, many complex considerations come into play:

- For ‘green field’ products there is brand risk if the implementation (e.g. customer experience) is not of the quality expected of the brand, or the delivery mechanism is patchy or unreliable.

- For existing products or services which are being revised, there will already be expectation hangover from the current product or service. Any established business will have to demonstrate that the new service is at least as good as the old or risk losing customers to competitors – a situation which almost always leads to the expectation of an MVP having to have feature parity with a long-established service implementation.

- For challengers in a mature marketplace (whether new or existing organisation), attracting customers and investors means a proposition with the same basic mechanics as your competitors from the outset, even if you have a more digital service, better product offering etc…

These types of situation, and the failure to fundamentally understand or accept the Viable element of MVP have led to a number of proposed alternatives such as the:

Minimum Valuable Product

Minimum Releasable Product

Minimum Viable Investment

Minimal Testable Product

Minimum Lovable Product

In each of these examples, we are changing the name only to fit a more challenging definition of viable – i.e. the definition or timeline is less desirable so let’s change the term!

All of these approaches attempt to solve problems with understanding the implementation of the MVP in specific situations. However, they have missed two fundamental truths

- ‘Viable’ is always situation dependent. What is viable for one product in an organisation may not be for another product in that very same organisation, and even less likely so a different organisation. A key aspect for defining your MVP therefore is defining what Viable means in your particular situation. What does this mean for our car? In a warm country, we could get away without a heater, in a dry country without windscreen wipers. Context is King (or Queen)

- Viability is a journey and might not be your first waypoint. Releasable, testable, loveable are all euphemisms for releasing before ‘viability’ because we typically don’t want to wait that long (for reasons we explored in the last blog as well as genuine opportunity) This is fine and valuable, but should not detract from the conversation as to what constitutes viability and when this is likely to occur. The challenge with hiding the point of viability with other terms is that often organisations will begin to lose focus on the product or proposition before viability is reached. This can lead to a suite of offerings that are less ‘good’ than originally envisioned, and we never really get to test the thing we originally set out to build

The viability quotient

One of the key difficulties in knowing what is viable in your context, is that you must have a very good understanding of what your organisation is trying to do, what is values and how it is trying to get there. The ‘V’ of MVP directly speaks to and challenges your understanding of organisational value. If you do not have this nailed down and universally understood, your definition of viability will only highlight a lack of cohesion. This will almost certainly make the ‘M’ of your MVP a bigger variable.

There are two elements of this puzzle – organisational vision and value definition is the first. This is a huge topic that we will come back to in future posts. The second is communication. To understand viability, it must be communicated explicitly and continuously. Our experience of helping define hundreds of MVP’s tells us that visualising the variables that effect viability, or the key levers you want to pull, is the best way of reaching consensus and exploring your MVP options. This will effectively support the creation of a path to viability and any waypoints along the journey.

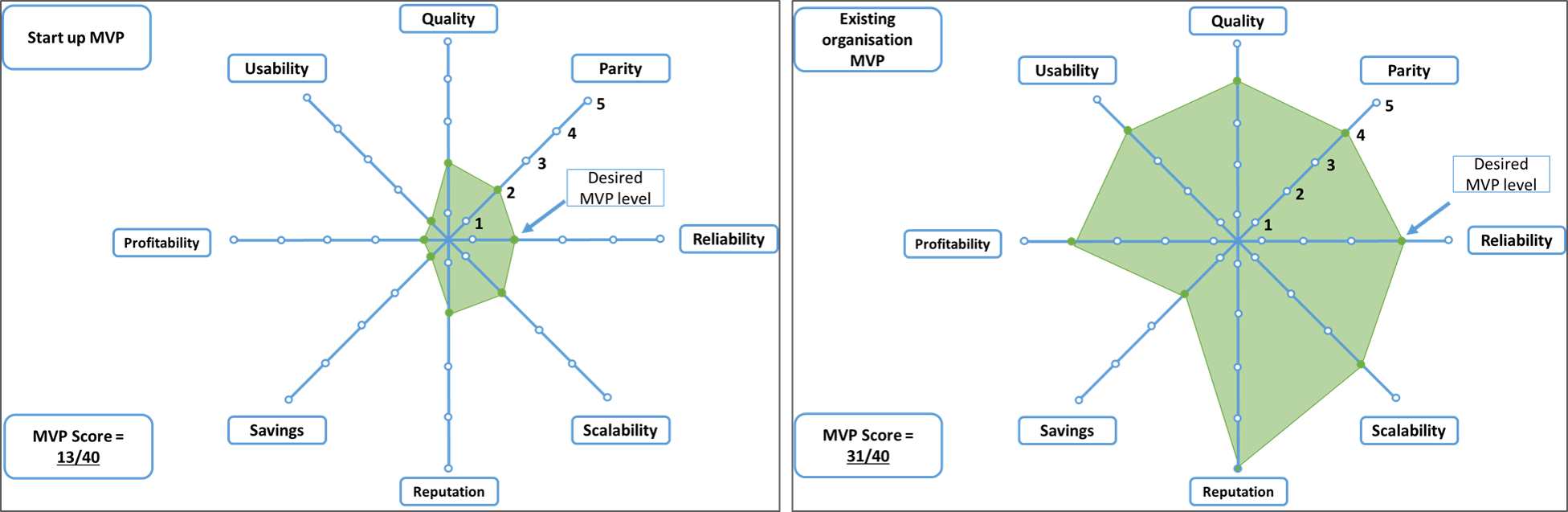

Our involvement in countless initiatives over many years has given us a broad insight into the things that are typically used to define what ‘’viable” means for a given product. We have used these elements as the axes of the two example spider diagrams shown below in order highlight one of the approaches we like to take while visualising the elements of viability. The examples also show the complexities of defining viability itself, as well as how the relative importance can change in different organisational environments.

The spider chart on the left is for a start-up organisation trialling a new proposition, the one on the right an existing organisation releasing a new delivery service for an existing, well established product. Because of the established nature of the product and its customer base, as well as overall brand credibility and the fact that there is an existing service for the product, the MVP for the existing organisation is quite large. Counting the points off the spider chart gives us a Viability Quotient (VQ) of 31 out of 40. The start-up conversely does not have the same magnitude of considerations as they have no established market presence and little to risk. As a result their MVP has VQ of just 13 out of 40.

The spider chart on the left is for a start-up organisation trialling a new proposition, the one on the right an existing organisation releasing a new delivery service for an existing, well established product. Because of the established nature of the product and its customer base, as well as overall brand credibility and the fact that there is an existing service for the product, the MVP for the existing organisation is quite large. Counting the points off the spider chart gives us a Viability Quotient (VQ) of 31 out of 40. The start-up conversely does not have the same magnitude of considerations as they have no established market presence and little to risk. As a result their MVP has VQ of just 13 out of 40.

It seems to be increasingly the case that the start-up MVP is considered “right” and the existing organisation MVP is “wrong”. However, this view completely ignores the very different environment and constraints that these differing types of organisations operate within.

Take a look at the spider diagrams again – if the start-up MVP takes 2-3 months as per the emerging mantra, then that for the established organisation will be more like 6 months. Does this mean that it is not their true Minimal Viable Product? Of course not! It simply reflects the comparative complexity of the environment in which their business operates.

Tools such as these help us to have honest conversations about what we are trying to create with the people whose expectations can influence us the most. Understanding what we really mean when we say ‘viable’ and not obfuscating this with alternative language, will give us a much better platform to talk about the ‘Minimal’ and help create a better roadmap to the proposition we want to get to our customers.

In the next bog, we’ll look at what we really mean when we say ‘product’, and how we can protect some of the genuinely larger MVP’s from unrealistic expectations some stakeholders will still have.