We’ve been thinking about MVP’s a lot recently and why they’re so challenging for so many organisations. We wanted to share our thoughts on this subject but quickly found that we had too much to say for one blog. We’re going to break it up into 3 blogs, the first one focussing on why ‘Minimum’ tends to be a limiting concept for many people. In future weeks, we’ll look at viability and organisational value, the definition of ‘product’ and we’ll also throw in some thoughts about how programmes can build in resilience through protection and momentum while the MVP’s are being delivered. Hope you enjoy this – please post your comments and feedback!

Part 1: When ‘Minimal Viable Products’ are less than Minimal

Negotiating the elusive Minimal Viable Product is a challenge for any organisation. Whether you’re delivering a new product or transforming the organisation, the MVP is more than just a work list or scoping exercise. It represents the goals, ambitions and expectations of the organisation and its people.

Many people focus on the ‘Minimal’ component. There seems to be an increasing view in the industry that “any MVP that can’t be delivered in 3 months is not worth doing” and the definition of success is suddenly narrowed to only one element of this concept. Identifying that a large ‘initial release’ is required is seen as somehow wrong and ‘counter Lean/Agile’.

Having worked on countless delivery projects, we have seen time and time again how misunderstanding both the scale of an MVP – The M – and what is meant by ‘viable’ can derail a big programme, paralyze decision making and sap the confidence and energy from delivery teams.

In this blog, we want to explore the concept and application of the MVP in more detail and ask what happens when your ‘Minimal’ product is bigger than you would like.

So, what’s wrong with the usual view of MVP?

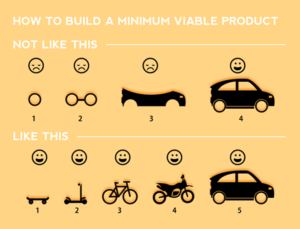

The typical description of an MVP is one that shows a clear, linear progression of value to a user – moving from a very basic proposition initially to one with increasing functionality and sophistication over time. An often seen example is that shown below – with a user moving from walking, through various modes of transport up to a car.

There is nothing wrong with this view of the world and it works well for delivery teams every day. However, it is based on 2 fundamental assumptions:

- There is a basic proposition that is more valuable to the consumer and business than the one they are already using – a bicycle is better than a scooter

- That this proposition can be easily and incrementally enhanced to add further value without adding costly complexity to the organisation or user – a scooter can be turned into a bicycle

Situations that tend to meet these assumptions are typically found when looking at ‘green field’ propositions and solutions. However, they are seldom found when working with mature organisations that have established offerings, or organisations wanting to challenge an existing, mature offering. Where a consumer already has a working car, why would they want to get rid of this and replace it with a scooter? Or even a bicycle?

Mature organisations typically already offer a car….or a fleet of cars….or an even more effective mass transport system! Introducing a car that is less ‘good’ than the existing ones to the fleet is not seen as an option – even if it is a little more reliable and cheaper to run and can be upgraded on the go. No-one wants to be the one to downgrade albeit temporarily…….even if there are benefits in the long run.

Re-platforming a business take this to extremes because the organisation is not looking to test a new proposition or market – it has already established these. It is looking to move from a fleet of rusting, unreliable cars to something more modern. This is often compounded by the fact that the business has been hiding the true state of the cars from its customers – and wants to wow them with the updates in service provided by the new fleet……so any downgrade just won’t do!

MVP in Mature Organisations

We have worked with a large number of organisations with mature product or service offerings who have looked to significantly transform their business and technology. Typically these organisations are looking to make significant changes to the way that they operate by taking advantage of advances in technology that allow them to react more effectively to the business environment.

Organisations in this situation can rarely afford to deliver new offerings with a small MVP. This is generally for two main reasons:

- They already have well developed and functionally rich offerings which they feel any degradation of will negatively impact their brand, impacting market share or share price

- The business value of an MVP which is less than their current platform is negligible – they do not need to test the business proposition – they need to deliver it better

However, all is not lost. The concept of the MVP is still valuable in these situations. The MVP itself is just bigger than we would expect to see in a start-up testing a new proposition. In re-platforming programmes, whether based around full Business Transformation or just Technical Transformation, it is not unusual for an MVP to take 9-15 months. While this may seem like a long time, and ‘not very Agile’, if this is how long it takes to build the minimum product that is viable in that business environment then that is how long it takes!

Rather than being less Agile, it is actually in these circumstances that we need to be more Agile. Focussing on what is really Minimal to deliver a Viable product will ensure that we getting the maximum value from Lean and Agile practices, such as building the right Product and testing early to ensure that it will be well accepted by customers.

Two of the biggest challenges when dealing with large MVPs are:

- Ensuring that the M really is for Minimal

- Demonstrating progress and value throughout the MVP

Dial “M” for Minimal

When carving out the initial MVP, we have to consider several key factors, including:

- What goals are we trying to meet in the overall project or programme?

- What goals are we trying to meet with the MVP?

- How mature is the product or service portfolio the organisation currently has?

- What are the customers’ expectations of the service or product?

There are also wider organisational considerations attached to the selection of an initial MVP such as the need to ‘prove out’ or ‘de-risk’ certain things, building a momentum of change and availability of key people and information.

Let’s take the public sector as an example. A government owned money lending organisation with upwards of 40 products, a complex stakeholder network and millions of customers is looking to transform their business and technology. The challenge: Identify a Minimal Viable Product that will begin the process of meeting the organisations key goal – building a new platform on which all 40 products can be delivered with incremental speed.

Feature richness and feature parity

If we consider the ‘Skateboard to Car’ model, this organisation currently had a car and could not use a reduced form of transport, though they could perhaps use a simpler car. In some organisations we have witnessed a desire for feature parity which is derived from fear. There is fear that customers will not accept what is perceived as reduced functionality, investors will not pay for a reduced feature set, and a sense that post-delivery enhancements will not materialise. This is a hangover from badly funded and badly run projects in the past.

Product Owners who have previously been burned by failing projects and promises of future work can view a backlog as a wish list and seek to surpass the current feature set.

We had lengthy discussions with the organisation about their desire for feature parity and came to the following understanding: This was an organisation of 40 cars – they would get no value from a reduced form of transport. However, it could be simpler type of car than those they already had (e.g. no sun roof or electric windows). Was the car less valuable because it could not be delivered within 3 months? Of course not! Especially knowing that the value was not only in the new car, but the learnings it provided for the remaining 39.

In future blogs about MVP’s for mature organisations and concepts, we’ll look at factors determining viability and we’ll share how we break this down to challenge organisational value. We will look at how you can build protection around larger MVP’s and describe what we mean by ‘product’.